Achromatic Bloom: Exploring Gray Scale with Natural Dyes

We often associate natural dyes with explosions of color – the fiery reds of madder, the joyous yellows of weld, the deep blues of indigo. The vibrant imagery they evoke is deeply ingrained in our understanding of textile art. But what if we shifted our perspective? What if we chose to explore the quiet beauty, the understated elegance, the subtle power of gray? The journey into grayscale with natural dyes is a meditative practice, a recalibration of perception, and a profound appreciation for nuance.

It’s a journey that reminds me of an antique accordion I once restored. It wasn’t a flashy, brightly-painted instrument. It was a simple, unassuming model, its original finish faded to a soft, pearlescent gray. Most restorers would have felt compelled to bring back its “true” color, to guess at what vibrancy it might have once held. But something in its muted tones – its history whispered in the wear and the fading – resonated deeply with me. I felt that stripping away more color would be a betrayal, a denial of its lived experience. The gray itself *was* its story. And so, I carefully cleaned and preserved it, allowing its quiet dignity to shine through.

The Philosophy of Gray in Textiles: Beyond Visual Display

The appreciation for gray extends far beyond aesthetics. Historically, gray and neutral tones have been associated with practicality, resilience, and even humility. Think of the work clothes of farmers and laborers – often dyed with readily available, muted plants. The focus wasn’t on visual display, but on durability and functionality. These were colors that wouldn't stain easily, wouldn't draw unnecessary attention, and would withstand the rigors of daily life. This connection to utility is a beautiful counterpoint to the often-romanticized notion of vibrant textile dyes. Often, achieving these muted tones required a deep understanding of earth pigments – a knowledge akin to understanding the story behind the colors, akin to documenting processes – a key aspect discussed in "rust’s requiem." This is a testament to the careful record-keeping essential to preserving these traditional methods.

Furthermore, many cultures have incorporated gray and neutral tones into their ceremonial dress and everyday attire to represent age, wisdom, or spiritual grounding. The simplicity and lack of ostentation can be a powerful statement in itself, transcending the need for bright, attention-grabbing hues. The deliberate choices made by dyers and artisans tell a story of intentionality and respect for materials, a narrative captured in every shade.

Natural Sources of Gray: A Pallet of Subtlety and Abundance

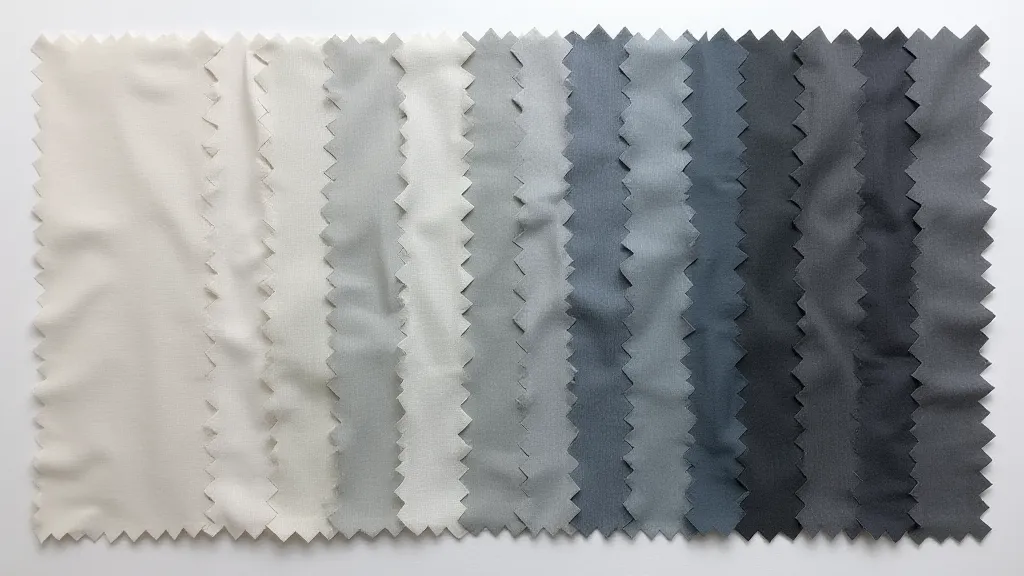

Creating a sophisticated grayscale palette with natural dyes requires a thoughtful approach and a deep understanding of plant chemistry. It's not simply about avoiding color; it's about strategically manipulating tannins, mordants, and dyeing processes to achieve the desired shades. Unlike the relative ease of obtaining bright reds or blues, graying is about subtraction, about harnessing the inherent properties of plants to create a complex interplay of brown, beige, and charcoal. The rich reds and vibrant hues that draw so much attention often come from carefully extracted pigments – a process that mirrors the focused efforts required to produce subtle grays.

Several plants offer surprisingly versatile graying potential. Oak galls, rich in tannins, are a cornerstone of many gray dye recipes. Their interaction with iron mordant (ferrous sulfate) produces a range of beautiful grays, from soft silver to deep charcoal. Walnut hulls offer a rich, warm brown that can be lightened with a combination of modifiers. Sumac, a readily available wild plant, also yields earthy browns that, when properly treated, can be transformed into subtle gray tones. Even the often-discarded skins of apples and pears can contribute a delicate, dusty gray when combined with the right mordanting process. The spectrum of possibilities, and the intricacies of each plant’s behavior, demand a meticulous and thoughtful approach – a process often requiring careful documentation to ensure repeatable results.

The Dance of Tannins and Mordants: Mastering the Interaction

The key to successful gray dyeing lies in the interplay between tannins and mordants. Tannins, found in many plants, act as the primary dye substance, bonding to the fiber. Mordants, typically metallic salts like iron (ferrous sulfate), aluminum (alum), or tin (stannous chloride), alter the color of the tannins, shifting them towards gray or brown. Iron, in particular, is incredibly effective at producing grays, but its use requires careful control, as it can easily darken the fabric too much. Mastering this process, understanding the subtle nuances of how iron interacts with different tannins – this speaks to a deep understanding of the chemistry involved. The deliberate use of these metallic salts, and their impact on color, can be complex and often requires a considered approach.

The ratio of tannin to mordant, the dyeing time, and the water temperature all significantly impact the final shade. Experimentation is crucial. Documenting your process meticulously – noting everything from the plant source and mordant concentration to the water temperature and dyeing time – will allow you to replicate successful results and refine your techniques. This methodical approach isn't just about achieving a specific color; it's about preserving knowledge and building upon the experience of generations of dyers.

Beyond the Obvious: Modifiers and Blending – Expanding the Palette

To expand the grayscale palette beyond the basic iron-tannin combination, modifiers can be employed. These are substances that alter the tone of the dye bath, creating variations in gray and brown. Vinegar can soften the harshness of iron, while a touch of soda ash can deepen the shade. The subtle addition of other natural dyes – even those considered “colorful” – can be surprisingly effective in creating unique and nuanced gray tones. A tiny bit of madder root, for example, might impart a warm, earthy undertone to an otherwise cool gray. Consider too, that creating these nuanced tones is a delicate balancing act, requiring an understanding of the underlying chemistry and a willingness to experiment. The process demands an observant eye and a sensitivity to the subtle shifts in color that occur as different substances interact.

Blending different dye baths – layering a light gray dye bath over a darker brown – can create complex and unpredictable results. This technique requires a deep understanding of the dyeing process and a willingness to embrace the unexpected. The beauty of natural dyeing lies, in part, in its inherent variability – a reminder that even in the pursuit of subtlety, there is room for surprise and discovery. The historical significance of these dyes, and their connection to the natural world, is something truly remarkable, evoking the power of rust’s requiem, a process intimately linked with iron and color transformation. Preserving this traditional knowledge is vital for future generations, as it connects us to the ingenuity and respect for the environment that characterized earlier dye practices.

Appreciating the Imperfection and the History: A Legacy of Craftsmanship

Working with natural dyes, especially when aiming for subtle grayscale tones, necessitates a shift in perspective. Unlike the predictability of synthetic dyes, natural dyes are inherently variable, influenced by factors such as plant origin, soil conditions, and water chemistry. Imperfections – slight variations in color, unevenness in the dye – are not flaws but rather evidence of the process, reminders of the natural world’s inherent complexity. These variations whisper tales of the environment where the plants grew, a story woven into the very fibers of the fabric.

Just as the antique accordion I restored held a history etched in its faded finish, textiles dyed with natural gray tones carry a story of their own. They are a testament to the enduring connection between humanity and the natural world, a celebration of craftsmanship, and a quiet rebellion against the relentless pursuit of uniformity. The longevity of these traditional methods speaks to their ingenuity and respect for the resources available. Preserving this knowledge is crucial for future generations. The nuanced understanding of plants, minerals, and their interactions is a legacy worth protecting.

Furthermore, the choice of plant material and dye processes often reflects a deep understanding of local ecosystems. Farmers and artisans would have selected plants that were readily available and sustainable, minimizing their impact on the environment. This mindful approach to resource management is a valuable lesson for contemporary textile practices. The legacy of these traditions is one of interconnectedness – between humans, plants, and the environment.

Working with natural dyes, especially when aiming for subtle grayscale tones, necessitates a shift in perspective. Unlike the predictability of synthetic dyes, natural dyes are inherently variable, influenced by factors such as plant origin, soil conditions, and water chemistry. Imperfections – slight variations in color, unevenness in the dye – are not flaws but rather evidence of the process, reminders of the natural world’s inherent complexity. These variations whisper tales of the environment where the plants grew, a story woven into the very fibers of the fabric.