Beyond the Hue: The Sensory Ecology of Dyeing

The scent of simmering madder root, the earthy aroma of woad steeping in water, the rustling of dried indigo leaves – these aren't just smells; they’re memories. They’re the echoes of generations who understood that textile dyeing wasn't simply a process of applying color, but a deeply sensorial experience, a conversation between humanity and the land. As a child, I was captivated by my grandmother’s weathered hands as she coaxed crimson from pomegranate peels, a ritual conducted in the soft afternoon light. She didn't explain the chemistry; she shared a feeling, a connection to the rhythm of the seasons and the enduring power of natural processes. That feeling – that holistic understanding – is what we risk losing in our increasingly industrialized world.

Modern dye houses, while efficient, often strip away this richness. The focus shifts to speed, uniformity, and minimizing waste – often at the expense of sensory depth. But the world's textile traditions tell a different story, a story woven with the threads of olfactory and tactile engagement. Think of the Scottish Highlands, where crofters traditionally dyed wool using woad, a process so deeply ingrained in the culture that the scent became synonymous with home. Imagine the vibrant hues of Andean textiles, born from cochineal insects harvested from cacti, the colors imbued with the warmth of the desert sun and the patient labor of skilled artisans. These weren't just colors; they were expressions of identity, of connection to place.

The Alchemy of Smell & Sound

The fragrance of natural dyes is as complex and nuanced as the colors they produce. Indigo, for instance, releases a pungent, earthy odor that changes dramatically as it ferments. Safflower offers a delicate floral note, while turmeric bursts with a warm, spicy fragrance. These scents aren't mere byproducts; they are integral to the dyeing process itself. The aroma can provide clues about the dye's progress, indicating when it’s reached optimal strength or when it's starting to break down.

The sounds of traditional dyeing are equally important. The gentle bubbling of a dye bath over a low fire, the rhythmic sloshing of fabric being immersed in dye, the crackling of dried plants being crushed – these sounds create a meditative atmosphere, a soundtrack to a deeply focused practice. It's a far cry from the sterile hum of a modern factory. The process often involves materials derived from plants and other organic compounds, many of which hold secrets related to their chemical properties and how they interact with textiles. Understanding these interactions, like those explored in relation to tannins, can be just as valuable as mastering the dyeing techniques themselves – a topic we delve deeper into in "The Language of Bark: Unveiling the Secrets of Tannins".

A Tapestry of Textures: Engaging the Touch

The tactile experience is another layer often overlooked. Natural fibers, like wool, cotton, and silk, respond differently to various dyes. The feel of the fabric changes as it absorbs the color, transforming from a raw, often slightly coarse material to something softer, richer, and more subtly textured. Working with natural dyes fosters a deeper understanding of these variations, a sensitivity to the nuanced interplay between dye and fiber.

Think of Japanese Shibori techniques, where cloth is intricately bound, stitched, and folded to create unique patterns. The process involves a constant, tactile engagement with the fabric, a feeling for its weight, its drape, and its response to pressure. Similarly, Andean weaving traditions often involve the use of natural fibers, often un-scoured, retaining the lanolin or other natural oils that contribute to a characteristic feel. The intricate manipulation of textiles to achieve patterns and textures is a craft form in itself – a focus of exploration in "Boundaries Dissolving: Shibori and the Art of Controlled Rupture". The way these techniques preserve history and tell a story echoes broader efforts to document these processes in detail - an exploration found within “The Unfolding Story: Documentation in Textile Dyes”.

Historical Context: Echoes of Craftsmanship

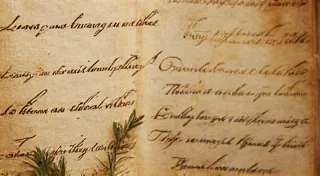

The history of textile dyeing is intertwined with the development of human civilization. Archaeological evidence suggests that humans have been using natural dyes for tens of thousands of years, long before the invention of written language. Early dye plants were often associated with religious significance, and dye-making was often a closely guarded secret, passed down through generations.

Consider the intricate block-printed cottons of India, which flourished under the Mughal Empire. These textiles were renowned for their vibrant colors and intricate designs, reflecting the artistic and cultural sophistication of the period. Or the richly dyed silks of Byzantium, which were prized throughout the medieval world. These weren’t just beautiful objects; they were symbols of power, wealth, and artistic achievement.

The Challenges & the Revival

The advent of synthetic dyes in the 19th century revolutionized the textile industry, offering a wider range of colors at lower costs. While this undoubtedly democratized access to colorful fabrics, it also led to a decline in traditional dyeing practices. The focus shifted away from natural materials and towards mass production, often with detrimental environmental consequences.

However, in recent years, there's been a renewed interest in traditional dyeing techniques. Driven by a desire for more sustainable and ethical practices, artisans and designers are rediscovering the beauty and complexity of natural dyes. This revival isn't just about aesthetics; it’s about reconnecting with our cultural heritage, supporting local communities, and minimizing our impact on the environment. This renewed focus isn’t just about color – it’s a holistic consideration of the resources and ethics involved in the process. Exploring the environmental impact and responsible sourcing is becoming increasingly crucial - as considered in "Dyed in the Shadows: The Ethics of Natural Resources".

Restoration & Collecting: A Sensory Appreciation

For those interested in antique textiles dyed with natural materials, appreciating the unique qualities of these pieces extends beyond their visual appeal. The subtle irregularities in color, the occasional 'bleeding' of dye, and the characteristic aroma (though often faint) are all testament to the natural processes involved.

Restoring these textiles requires a delicate touch. Harsh chemicals can strip away the natural dyes and damage the fibers. Often, the best approach is to clean the fabric gently, avoid direct sunlight, and appreciate the patina of age. Similarly, collecting antique dyed textiles allows for a deeper understanding of history and a sensory engagement rarely available in contemporary material culture.

The Enduring Appeal of Rooted Hues

The process of extracting color from the earth – the careful selection of plants, the patient simmering and steeping – creates a link to the landscape that transcends mere aesthetics. The color itself isn’t simply a pigment, but a concentrated essence of place, imbued with the energy of the sun and soil. Consider the deep, resonant colors derived from the madder root, a plant whose presence speaks of ancient agricultural practices and a profound understanding of the natural world. The cultural and historical significance of this cornerstone dye is well explored in “The Echo of Madder: A Rooted Palette”.

Beyond Color: A Holistic Perspective

The sensory ecology of dyeing—the smells, sounds, and textures—is an integral part of the craft. It’s a reminder that textile production is more than just a technical process; it’s a deeply human endeavor, a conversation between people, plants, and the land. By engaging all of our senses, we can rediscover the magic of traditional dyeing techniques and appreciate the artistry of generations past. It’s a shift from viewing textiles as mere commodities to understanding them as sensory experiences, carriers of history, and expressions of cultural identity. The true beauty lies not just in the hue, but in the holistic tapestry of the entire process.